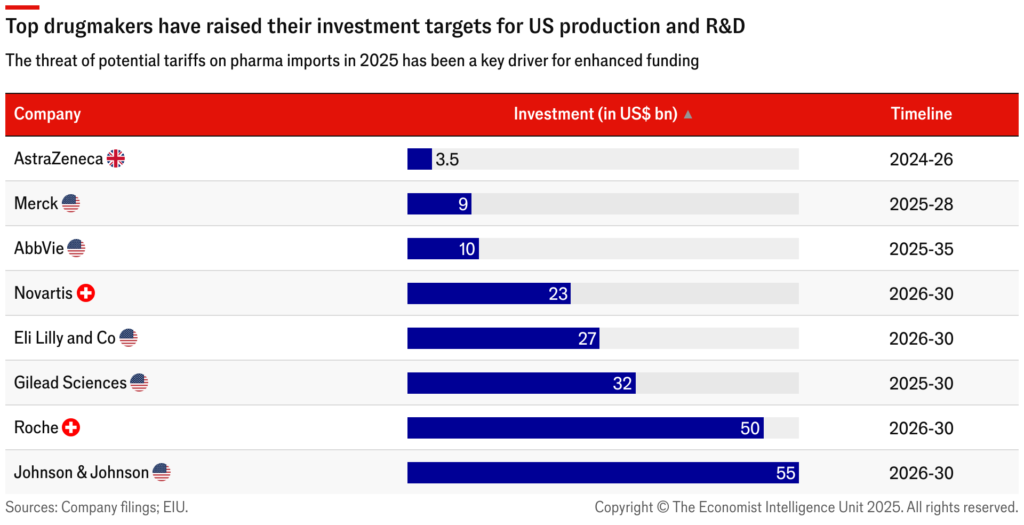

Merck and AstraZeneca’s decisions reflect a broader industry exodus as drugmakers cite government undervaluation, lack of competitive environment and prioritise US investment.

The UK’s pharmaceutical sector crisis has dramatically deepened this week, with AstraZeneca pausing its entire £650m UK investment package, completing a devastating week that began with US pharmaceutical giant Merck scrapping plans for a £1bn research centre in London.

AstraZeneca’s decision means none of its much-trumpeted investment programme—originally announced in March 2024—is currently proceeding. The latest setback involves pausing a planned £200m expansion of its Cambridge research site that was expected to create 1,000 jobs, following January’s cancellation of a £450m vaccine manufacturing facility in Speke, Merseyside.

The coordinated nature of this week’s announcements suggests a fundamental shift in how pharmaceutical companies view the UK market. Eli Lilly has also placed its planned £279m London gateway lab “on hold,” while French pharmaceutical giant Sanofi declared that “any substantial inward investment into the UK is currently on pause until we see tangible progress towards making the life sciences environment internationally competitive.”

The UK is not internationally competitive

“Simply put, the UK is not internationally competitive,” Merck told the Financial Times, adding that the move “reflects the challenges of the UK not making meaningful progress towards addressing the lack of investment in the life science industry and the overall undervaluation of innovative medicines and vaccines by successive UK governments”

The company, known as MSD in Europe, will relocate its UK research operations to existing sites, primarily in the United States, where the Trump administration has been pressuring pharmaceutical companies to increase domestic investment

Merck will also vacate existing laboratories at the London Bioscience Innovation Centre and the Francis Crick Institute by the end of the year.

Companies prioritising US investment over UK

The stark contrast between UK divestment and US investment reveals the scale of the challenge facing Britain. While AstraZeneca pauses its entire UK programme, the British-headquartered company announced in July a $50bn investment in the US by 2030, funding new drug manufacturing in Virginia and expanding laboratories across Maryland, Massachusetts, California, Indiana and Texas.

AstraZeneca CEO Pascal Soriot described the US commitment as underpinning the company’s “belief in America’s innovation in biopharmaceuticals,” and has reportedly considered moving the company’s stock listing from London to New York.

Merck’s UK withdrawal aligns with its broader $9bn US investment plan through 2028, including a $1bn North Carolina facility opened in March and another $1bn Delaware plant for its cancer drug Keytruda, expected to create over 4,500 jobs.

This trend reflects mounting pressure from President Trump, who has threatened tariffs of up to 250% on pharmaceutical imports and signed executive orders aimed at reducing drug prices while pressuring companies to increase domestic investment.

Source: The Economist Intelligence Unit

Pricing Disputes and Government Relations

The industry’s frustrations have been building over successive pricing disputes with the UK government. Last month, negotiations between drugmakers and Health Secretary Wes Streeting over a branded medicine pricing deal collapsed after the two sides could not agree on the size of rebates paid back to the government.

Under the current voluntary pricing and access scheme, companies must pay back a portion of revenue from newer, branded drugs. The rebate rate soared unexpectedly to 22.9% in 2025—well above the anticipated 15%—forcing pharmaceutical companies to return nearly a quarter of their UK sales to the state-run health system. This compares unfavorably with rebate rates of 5.7% in France and 7% in Germany.

Paul Naish, Sanofi’s UK head of market access, told The Guardian that Britain needed a “proper plan from the Treasury” for life sciences, arguing the country had become “not a good place” to develop or sell drugs.

Richard Torbett, chief executive of the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI), described Merck’s decision as “a real blow” to the UK’s life sciences ambitions. “This news must be used as an opportunity to reflect on what factors are driving companies to make such difficult decisions, and what this country can do to ensure it is attracting the high-quality investment we need and not driving it away,” he said.

Declining Competitiveness by the Numbers

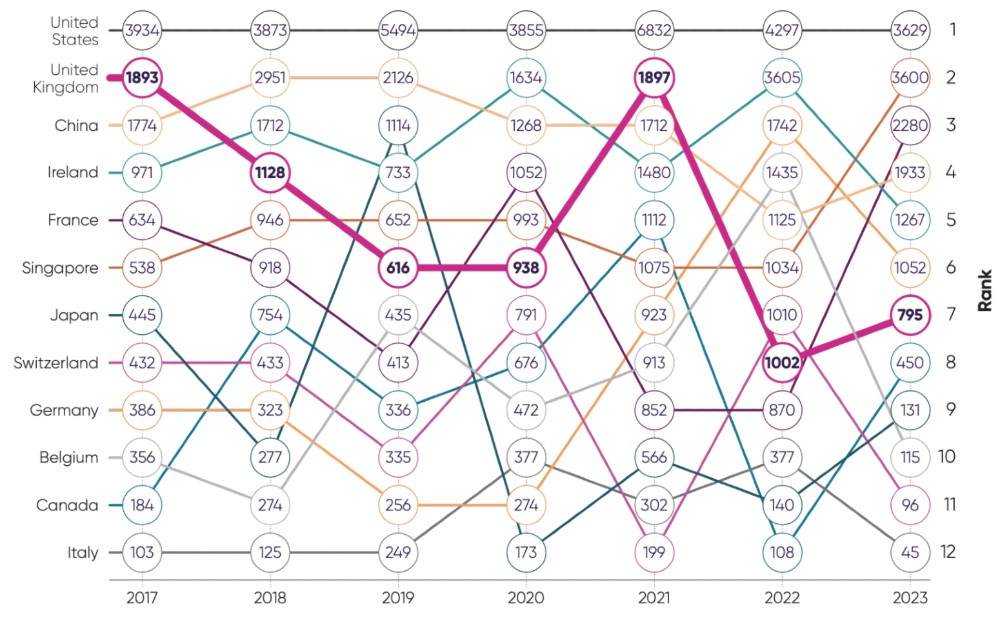

New research from the ABPI and consulting firm PwC reveals the extent of the UK’s declining competitiveness in pharmaceutical investment. Foreign direct investment in UK life sciences fell 58% to £795m between 2017 and 2023, causing the country to drop from second place globally in 2017 to seventh place in 2023.

Inward life sciences foreign direct investment (£ million)

According to the ABPI, investment in life sciences research and development has significantly underperformed against global trends since 2018. The rate of R&D investment growth fell to just 1.9% annually from 2020, down from 6.3% in the three preceding years and lagging behind the global average of 6.6%. In 2023, R&D investment by the pharmaceutical industry actually declined by nearly £100m.

The UK has also lost ground in clinical trials of new medicines, ranking eighth for late-stage industry trials in 2023, down from fourth place in 2017. Perhaps most concerningly for patients, only 37% of new medicines are made fully available for their licensed indications in the UK, compared with 90% in Germany.

Impact on Patients and Access

The investment flight has real-world consequences for patient access to cutting-edge treatments. ABPI data shows that more than 60 medicines either did not launch in the UK or were delayed between 2019-20 and 2022-23.

Rippon Ubhi, who runs Sanofi’s UK and Ireland business, said the findings “paint a concerning picture for UK patients and our economy. The UK is increasingly being viewed as ‘uninvestable’ in global boardrooms due to unprecedented NHS clawback rates and restrictive patient access to medicines”.

Johan Kahlström, UK head of Swiss pharmaceutical firm Novartis, has similarly warned that high costs mean the UK is “largely uninvestable,” while noting that his company has “already been unable to launch several medicines” in the country due to the “declining competitiveness” of the UK market.

Government Response Under Pressure

A spokesperson for the UK government defended the UK’s investment climate, stating: “The UK has become the most attractive place to invest in the world, but we know there is more work to do. We recognise that this will be concerning news for MSD employees and the government stands ready to support those affected”.

However, the coordinated nature of this week’s announcements has intensified pressure on Sir Keir Starmer’s administration, which has identified life sciences as one of eight “growth-driving” sectors in its flagship industrial strategy. The government has set ambitious targets to position the UK as the leading life sciences economy in Europe by 2030 and third globally by 2035.

Officials at the Department of Health, reportedly concerned after the scale of pharmaceutical pullbacks, are said to want to reopen pricing negotiations with the industry that collapsed in August.

Dr David Roblin, chief executive of London-based biotechnology company Relation Therapeutics, argued that fundamental strengths remain. “The academic environment in the UK continues to produce innovative ideas and people to run with those ideas, which attracts foreign investment. The environment to do research is still outstanding: we’ve got great academics, the NHS does provide a research platform,”

However, he acknowledged that the political landscape has shifted dramatically. “What has changed was the political landscape in the US which big pharma has to respond to, because the US remains the largest market for pharmaceuticals on earth” (Source: BBC).

Merck’s warning that “more and more companies will be making these sorts of decisions” unless the operating environment improves suggests the UK faces a critical juncture in maintaining its position as a global life sciences hub.